It is a plausible assertion that Zaha Hadid (1950 – 2016) was the only female architect the general public could name or recognise. Formidable, venerated and brilliant, she was indeed the architectural world’s grande dame.

Zaha Hadid was born in 1950 in Baghdad, Iraq’s capital city. She studied mathematics at the American University of Beirut and moved to London in 1972 to read architecture at the Architectural Association. Graduating in 1977, Hadid worked with former professors Rem Koolhaas and Elia Zenghelis at the Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). She then established the eponymous London-based Zaha Hadid Architects in 1979.

Suprematist Influences

Early in her career, Hadid was inspired by St. Petersburg’s avant-garde artists and their pursuance of Suprematism1 in paintings and architectural schemes. As a student at the Architectural Association, Hadid worked to realise ideas, such as fragmentation and layering, that had not been achieved by the Suprematists themselves. She would use isometric and perspective drawing techniques, as once practiced by the Suprematists, to bring irrational spaces to fruition. Hadid was the first to apply principles of Suprematism in a three-dimensional space that would ultimately lead to a workable architectural scheme. (Giovannini, 2004)

A Shift Away from Modernism

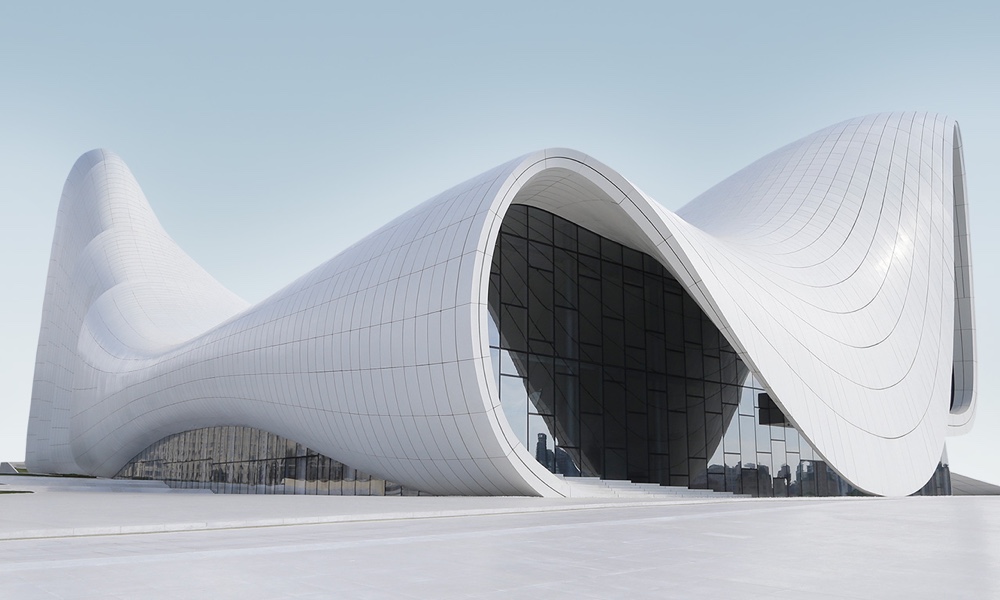

Hadid’s architecture would in many ways mark a shift from modernism’s functionalist (Bauhaus) worldview to an era of complex forms, their shapes virtually defying gravity. She would stretch space, distort proportions, mock convention and eschew the bounds imposed by reality. Still, her concepts were difficult to make real and would push the limits of practicality, usually with associated spiraling budgets. Clients who wanted Hadid no doubt realised that cost was not her top priority; after all, she was giving them an architectural tour de force that would last for many generations. “Her eventual success came when her celebrity meant that clients had to accept her on her own terms: either give what it takes to realise a Hadid or go elsewhere,” (Moore, 2016).

Photos by Hufton + Crow via DesignApplause.

In their final state, Hadid’s buildings would appear as spectacular, dizzying and overt compositions, transforming our ideas of the future and sparking much debate within and outside architecture. For example, questions were posited about the purpose of her work: to assuage grandiose notions of self-importance or provide dynamic and liberating spaces? In his 2004 laureate essay on Hadid (for the Pritzker Architecture Prize), Joseph Giovannini contemplated: “The aesthetic refinement of her designs, their very beauty, belies the fact that Hadid is committed to cultivating and enhancing the urban environment… she opens geometries to invite the city into her buildings [as a form of social activism]” (Giovannini, 2004).

Controversies and Debacles

Hadid was lambasted and faced prejudice owing to the fact she was a woman, born in Iraq, now powerful and successful, and operating in a predominantly male environment. She previously asserted: “I’m a woman and that’s a problem for some people, I’m a foreigner, and I do work which is not normative, not what they expect” (Moore, 2016). Hadid encountered varied controversies and debacles: the construction of her ill-fated Cardiff Bay Opera House was stopped and her plans for Tokyo’s 2020 Olympic Stadium were scrapped. In the designing and building of the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, she was accused of colluding with tyranny. The building was named after Azerbaijan’s former brutal dictator and was commissioned by his son, the country’s current brutal dictator (Moore, 2016). Perhaps as a consequence of her many trials, there was a time when she would say “am I bovvered?”, emulating a character by British comedienne Catherine Tate (Moore, 2016).

The Celebrated ‘Starchitect’

Zaha Hadid was one of the first so-called ‘starchitects’, her high-profile status, perceived ego and glut of sleek and shiny iconic buildings the perfect fit for this epithet. In his appreciation piece on Hadid, the Observer’s architecture critic Rowan Moore noted: “Hadid, as remarkable in her person and her personality as in her designs, was perfect for the role [of starchitect]” (Moore, 2016).

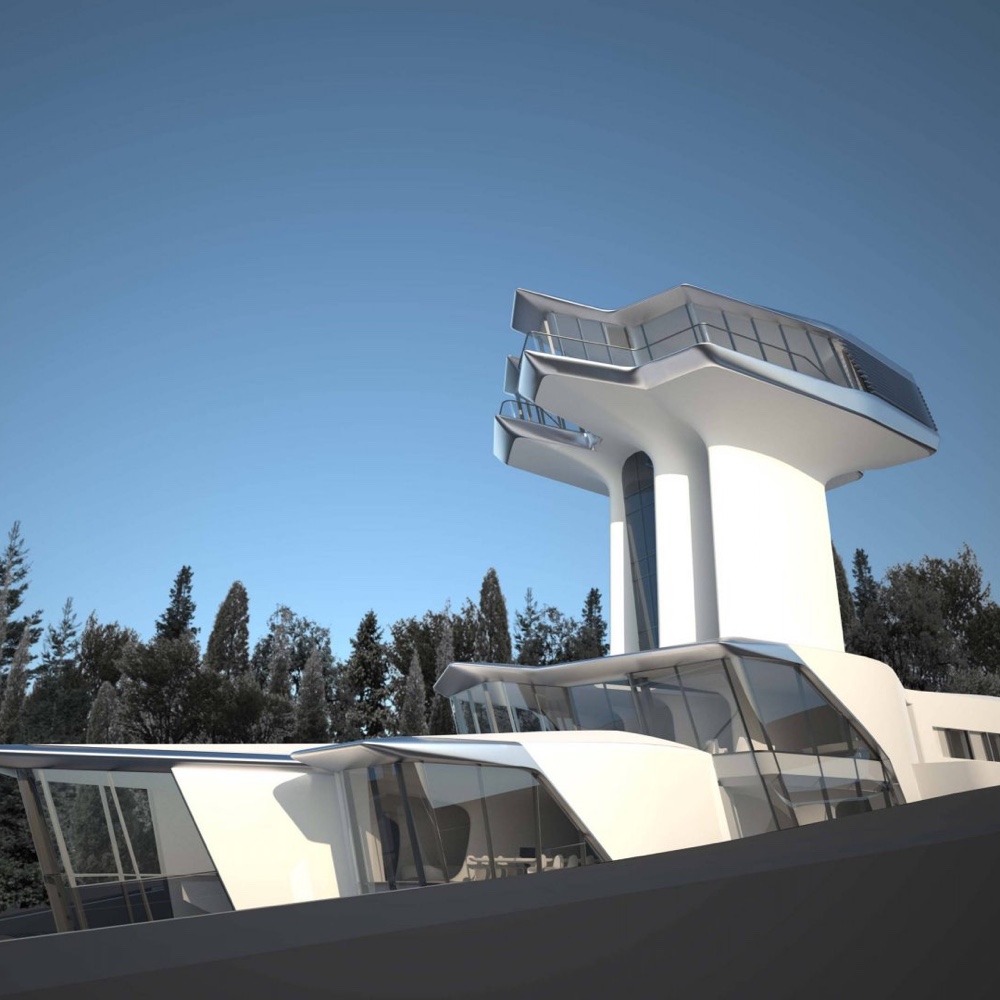

Images © Iwan Baan via ArchDaily.

Images © Luke Hayes via ArchDaily.

A celebrated and prodigious architect, Zaha Hadid was the recipient of many awards and accolades. She was the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Prize in 2004. She won the UK RIBA Stirling Prize in two consecutive years: in 2010 for the MAXXI Museum in Rome and in 2011 for the Evelyn Grace Academy in south London. More recently, RIBA’s 2016 Royal Gold Medal was bestowed on Hadid, an accolade given in recognition of a significant contribution to architecture. She was indeed the first woman to be awarded this honour in her own right. In receiving the medal, Hadid observed: “Part of architecture’s job is to make people feel good in the spaces where we live, go to school or where we work – so we must be committed to raising standards. Housing, schools and other vital public buildings have always been based on the concept of minimal existence – that shouldn’t be the case today. Architects now have the skills and tools to address these critical issues” (Source: Dezeen).

Love her work or hate it, Zaha Hadid had the power to divide opinion. She was committed to form and fluidity. She was grandiose and pragmatic. She was revered and doubtless feared. A trailblazer, she was architecture’s grande dame.

Tributes to Zaha Hadid

Just a few of the architects paying tribute to Zaha Hadid:

Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas: “I see her work not necessarily as an exciting form of Western architecture and a development of Western architecture, but really something fundamentally different. That is what I think may be her biggest achievement in the end… I think she was obviously very proud of what she achieved as a woman but in the end, there’s no need for special pleading or for treating her architecture on that basis. Yes I think she made an enormous contribution as a woman, but her greatest contribution is as an architect.” (Source: Dezeen)

Japanese architect Kengo Kuma: “Dame Zaha Hadid was a great architect who led the world of contemporary architecture after the era of Postmodernism.” (Source: Dezeen)

British architect Norman Foster: “I think it was Zaha’s triumph to go beyond the beautiful graphic visions of her sculptural approach to architecture into reality that so upset some of her critics. She was an individual of great courage, conviction and tenacity. It is rare to find these qualities tied to a free creative spirit.” (Source: Dezeen)

Further works by Zaha Hadid

References:

Giovannini, J. (2004). The Architecture of Zaha Hadid. The Pritzker Architecture Prize, Retrieved from http://www.pritzkerprize.com

Moore, R. (2016, 3 April). Zaha Hadid, 1950-2016: an appreciation. The Guardian, Retrived from http://www.theguardian.com/uk

1Suprematism is defined in the Apple Dictionary as: “the Russian abstract art movement developed by [Russian Artist] Kazimir Malevich circa 1915, characterized by simple geometrical shapes [such as circles, squares, lines and rectangles] and associated with ideas of spiritual purity.”