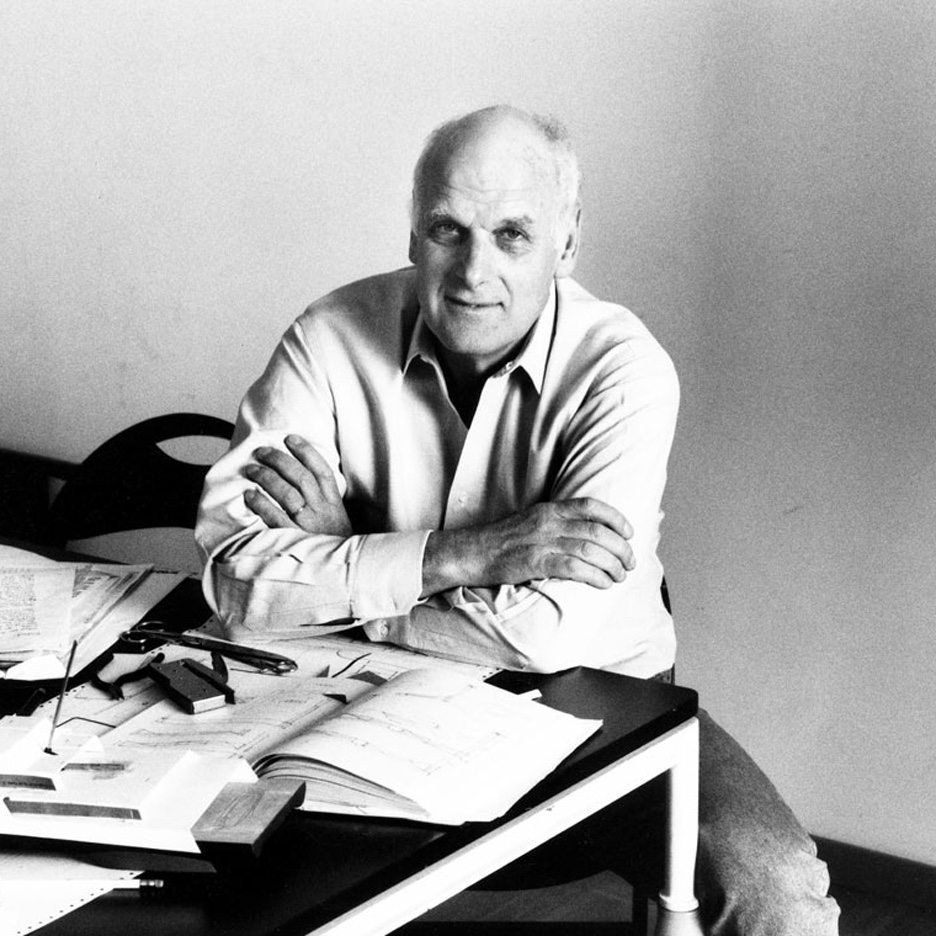

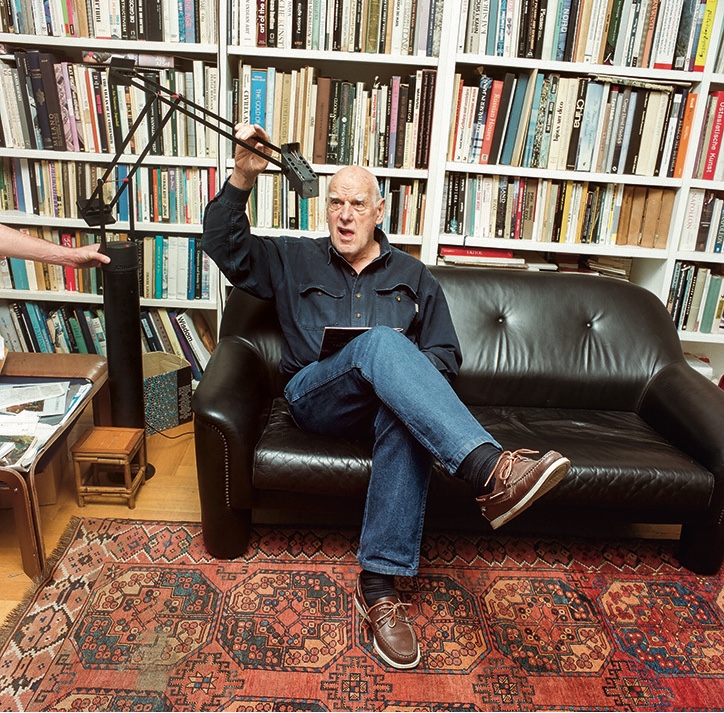

Richard Sapper was a German industrial designer whose contribution to the genre was no less than prodigious. Born in Munich on 30 May 1932, Sapper was based in Milan for the majority of his remarkable career. As a result, his work would often pair German manufacturing precision with Italian design flair.

Early Days

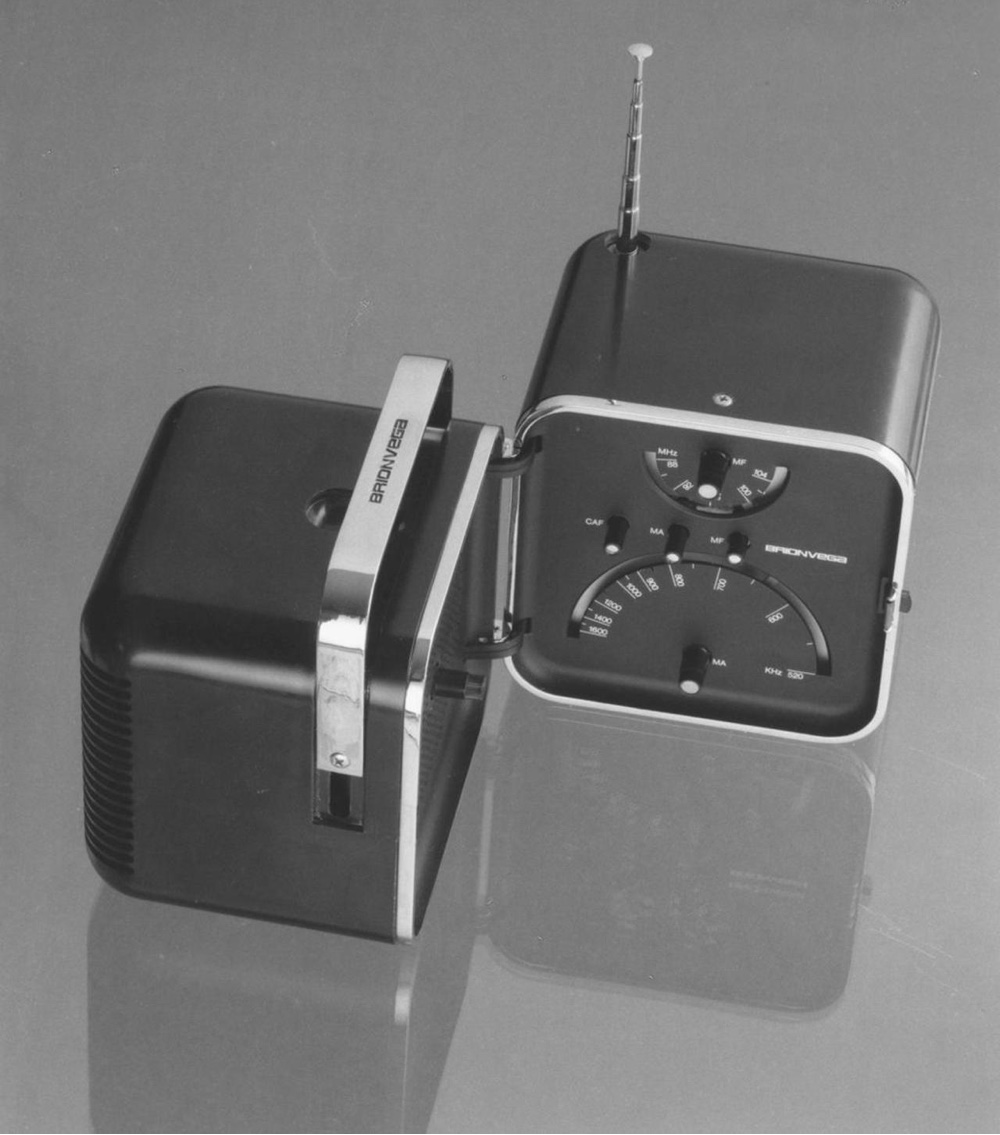

Richard Sapper’s career began in the styling department of Daimler Benz in Stuttgart. He moved to Milan in 1958, where he apprenticed under the influential Italian architect Gio Ponti. Sapper then worked in the design division of La Rinascente, the pioneering upscale Italian department store. Within a year he began working independently, opening a studio in Milan in 1959 and operating as a consultant with various highly regarded companies. At Brionvega (an Italian electronics firm), Sapper designed a series of televisions and radios in conjunction with Italian architect and designer Marco Zanuso. Sapper and Zanuso’s partnership was a highly productive venture. Lasting on and off for eighteen years, it would result in several groundbreaking designs, including: the little Doney television set (1962) and the TS502 radio (1963) for Brionvega. Such items were sculptural pieces, both truly innovative and aesthetic at that same time (and remaining so today).

Utilitarian Design with Characteristic Details

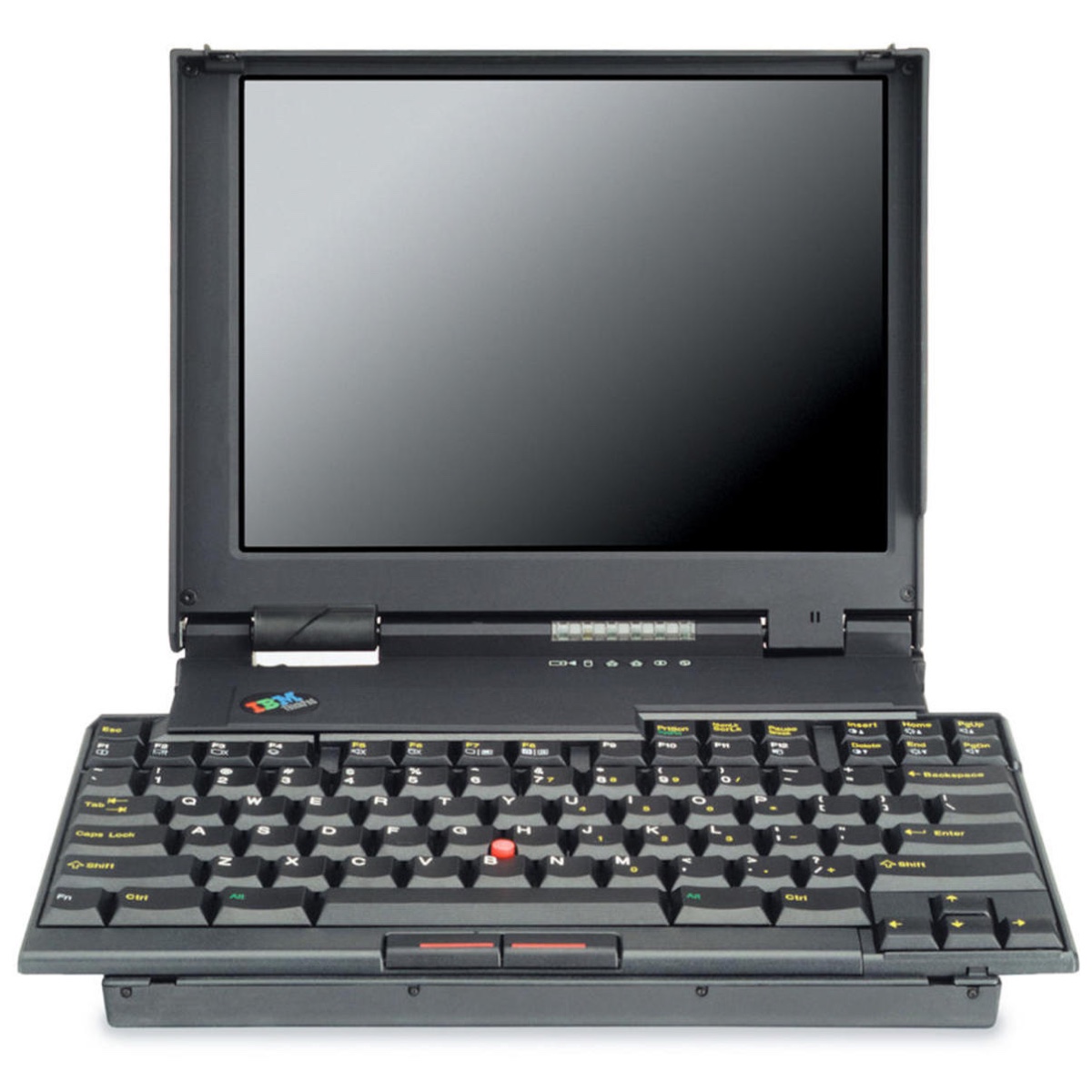

Richard Sapper’s industrious nature and creative mind ensured he was a man whose talents were invariably in demand. At Italian automaker Fiat, Sapper worked on transportation-related projects, and at IBM, he was appointed as the brand’s principal industrial design consultant. Along with designers Sam Lucente and John Karidis, Sapper designed the IBM ThinkPad 701 laptop in 1996 (as well as other computer designs). Indeed, Steve Jobs attempted to entice Sapper to work at Apple. Not wishing to move to California and having various projects to complete, Sapper declined (and Jonathan Ive went on to fulfill the role). The Tizio desk lamp (1972) for Artemide is one of Sapper’s best known designs. A strikingly modern and utilitarian object, the lamp’s adjustable counterbalanced arms ensure precise positioning of the light source. Sapper was not necessarily driven by aesthetic or style, yet he would often add small characteristic details to his designs. For example, joints on the Tizio lamp are bright red, and the ThinkPad laptop’s mouse button is coloured red.

Richard Sapper and Alessi

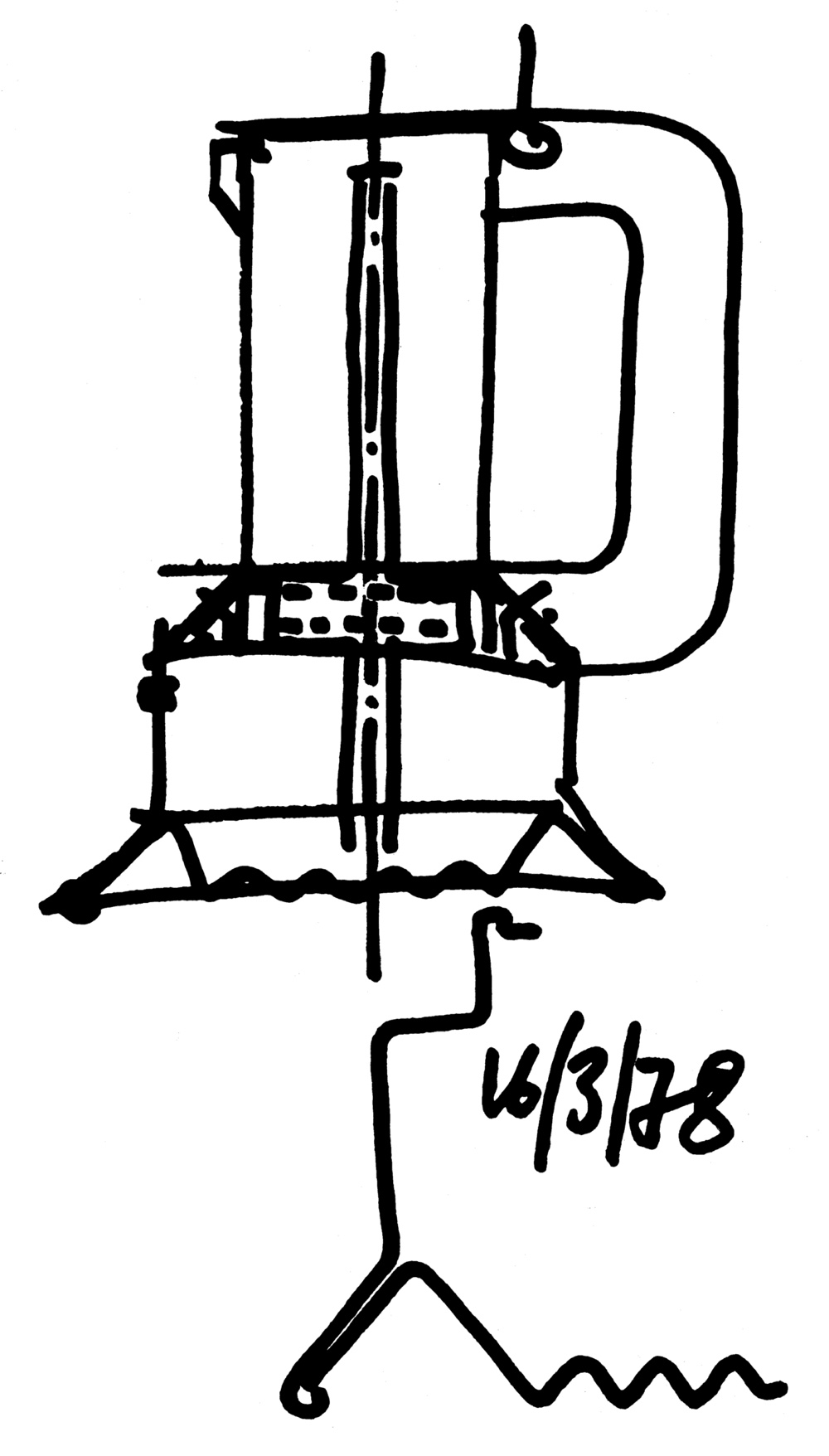

Alessi was one of Richard Sapper’s most important clients. A notable Sapper design for the brand was his 9090 espresso coffee maker. In an interview with online design magazine Dezeen, Alessi’s president, Alberto Alessi, said of Sapper’s iconic design that it was: “[an] homage [made to his] other grandfather, the father of [his] mother, Mr Alfonso Bialetti… the inventor, the designer and the producer of the first Italian espresso maker [the Bialetti Moka Express]” (Source: Dezeen). Designed in 1978, Sapper’s 9090 espresso coffee maker included the invention of a clever leverage to open the appliance and an all-important non-drip spout. It was the first Alessi project for the kitchen, the company’s first Compasso d’Oro award (conferred in 1979) and its first object to be inducted into the Permanent Design Collection at MoMA. Alessi has now sold around two million units of the 9090.

The 9091 (1983) was Alessi’s first design-led kettle. The kettle’s brass whistle produces a short and pleasant melody and is Richard Sapper’s rather humorous nod to postmodernism.

Accolades

Richard Sapper’s list of awards is extensive. He won the Compasso d’Oro on no fewer than ten occasions (an industrial design award, the Compasso d’Oro originated in Italy in 1954). In 2014, the Associazione per il Disegno Industriale – hosts of the Compass d’Oro – once again presented the award to Sapper, honouring his career achievements. Sapper’s designs are included in the permanent collections of many of the world’s most distinguished museums: from New York’s MoMA to London’s Victoria & Albert Museum to the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

For all of his accomplishments, Richard Sapper’s work often went unnoticed. In 2013, he launched a personal website that catalogues his considerable design achievements. Sapper once observed: “I’ve been working in design for over 50 years and most people still don’t know my work.” (Source: Dezeen) His body of work epitomises the bold and the beautiful, and is wholly concerned with the betterment of society in a world where rampant consumerism reigns. Of design today, Sapper remarked: “There are certainly too many products and too many designers, and the idea behind design has changed. Today it’s all [about] money. Back then it was just an interest in producing something beautiful.” He went on to say: “… there is more good design now, but really good design was rare when I started and is still rare now” (Source: Dezeen).

Richard Sapper died on 31 December 2015. Thankfully, his legacy lives on.

Bibliography:

Richard Sapper Biography. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://richardsapperdesign.com/about

Sparke, P. (2016, 8 January). Richard Sapper. The Guardian, Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/jan/08/richard-sapper