Harry Seidler (1923 – 2006) was born in Vienna, Austria. His architectural education took him first to England: escaping the Nazi occupation of Austria, he attended a polytechnic school in Cambridge. Following the outbreak of WWII, Seidler – an alien from an enemy country – was interned in England and the Isle of Man, then sent to Canada. Paroled in 1941, he continued his studies at the University of Manitoba in Western Canada. Graduating in 1944, Seidler won a scholarship to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design and attended Walter Gropius’s masterclass from 1945-46.

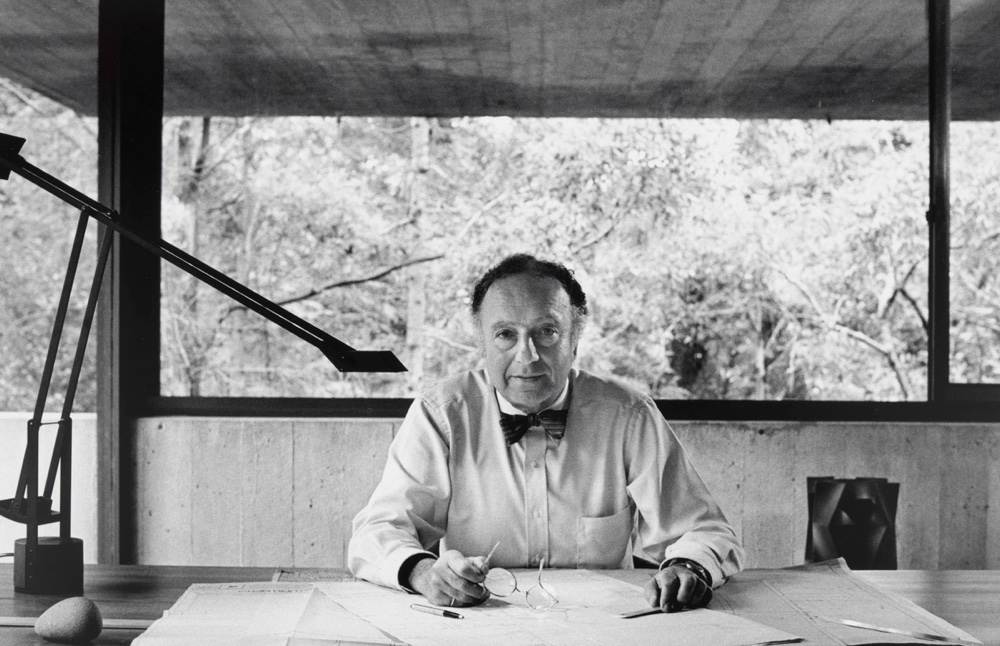

Harry Seidler, Killara, Sydney (1984). Photo by David Moore © National Portrait Gallery 2016.

Walter Gropius, the first director of the Bauhaus, instilled in his students the idea that they should occasion vital changes to the physical environment, so ensuring the betterment of a manmade world. As well as Walter Gropius, Seidler worked with other prominent architects and visionary protagonists of international modernism. In 1946-48, he was the first assistant to Marcel Breuer, one-time head of the carpentry workshop at the Bauhaus and a veritable master of modernism. In 1948, with the excitement stirred by Brazil’s new architecture, Seidler travelled to Rio where he worked with the distinguished Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer.

Rose Seidler House

Harry Seidler moved to Australia in 1948 where he applied his learned ideals on modernist methodology. At the request of his mother, Seidler’s first commission was to design a house for his parents. It became known as the Rose Seidler House (now a public museum) and was an exceptionally modernist dwelling in Australia at that time, drawing much attention and acclamation.

Rose Seidler House. Image © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

Deck at Rose Seidler House in April 2011. Photograph © Phyllis Wong, Historic Houses Trust of NSW. Image via Sydney Living Museums.

Australia Square

Harry Seidler was a leading figure in laying the foundations for post-war modern design and architecture in Australia. His architecture was truly an art form, both simple and functional in its manifestation. An exceptional talent, Seidler had a marked impact on the development of Sydney’s skyline. For more than half a century, he would design varied bold and modern structures in Australia and internationally.

Australia Square in the context of Sydney Harbour. Image © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

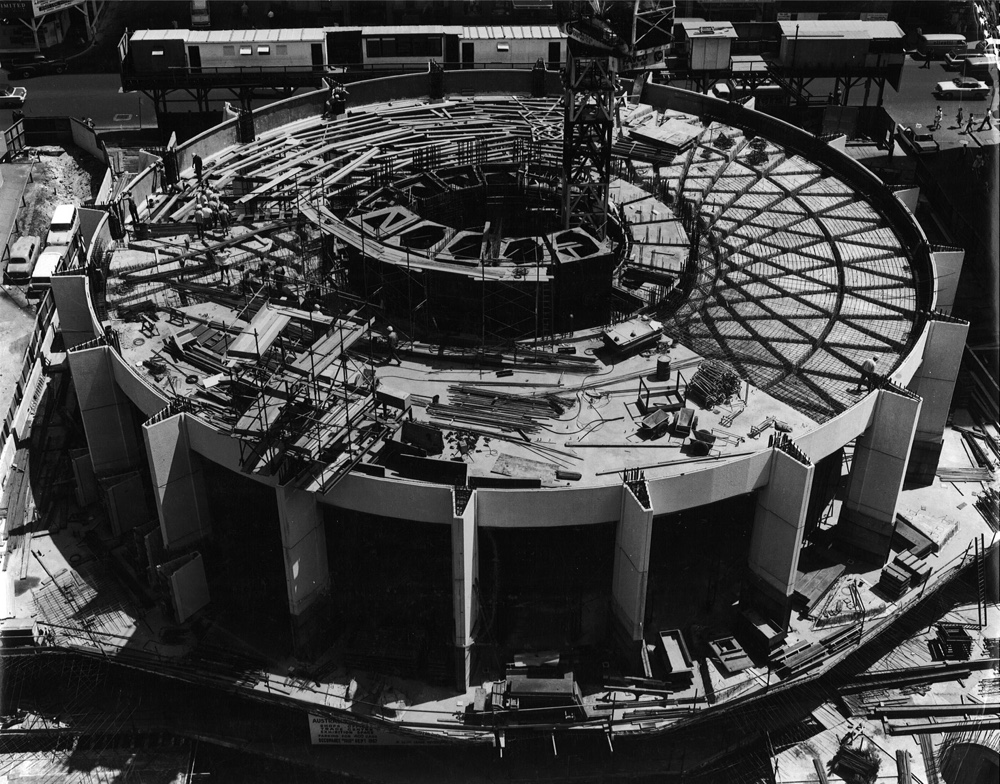

In 1960, Seidler was asked to design Australia Square, an ambitious development in Sydney’s central business district. Work commenced on the project in 1961, with plans for a tower, plaza, retail and parking in the mix. Australia Square was completed in 1967; the 50-storey circular Tower Building was Australia’s first skyscraper and at that time, the world’s tallest lightweight concrete building. This modernist icon occupied just 25 percent of the Australia Square site, with the remainder of the area given over to a public plaza.

Rib structure used in the Tower Building at Australia Square. Image © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

Public plaza and restaurants. Image © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

Australia Square, Sydney, 2007. Image by Elekhh via Wikimedia Commons.

Harry and Penelope Seidler house

The Harry and Penelope Seidler house is a perfect example of the close bond that can exist between concrete and nature. Nestled amid a cornucopia of lush Australian vegetation and ensconced upon a steep bushland site in Killara on Sydney’s Upper North Shore, this brutalist residence is an architectural masterpiece. Designed and built in the 1960s by Harry and Penelope Seidler, the house adopted a functionalist style of architecture and is the epitome of modernist ideals. Honest, exhilarating and raw, the Seidler house reflects brutalism on an intimate human scale, its strong forms both exalted and elegant. In Australia, the home is widely considered an eminent example of a house in the brutalist style, though Harry Seidler did reject the ‘brutalist’ label.

Photo by Ross Honeysett © 2016 MONOCLE.

The Seidler house comprises four half-storey levels that follow the landscape’s sloping and rocky typology. A clever open-plan layout ensures that differing perspectives and vistas are offered throughout. The home’s frame and roof have been built using concrete, and ceilings are made from Tasmanian mountain ash. Bauhaus influences and aesthetics are in evidence across the property, remaining as progressive today as when the house was first built.

Photos by Ross Honeysett © 2016 MONOCLE.

As a piece of architecture, the Harry and Penelope Seidler house stands with integrity, a testament to the wonder and veracity of modernist principles. It is a truly sublime family home.

Penelope Seidler at the Killara House. Photo by Harry Seidler, 1967. Courtesy of and © Penelope Seidler. Image via Sydney Living Museums.

Seidler home, Killara, Sydney. Image by Sardaka via Wikimedia Commons.

Other works by Harry Seidler

As well as the aforementioned design triumphs, there are many other important architectural accomplishments by Harry Seidler. Several favourites include:

MLC Centre. Designed 1972-75. An imposing city centre precast concrete office tower in Sydney. Image © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

Hillside Housing. Designed 1979-82. A resort village with 55 holiday houses located in Kooralbyn, Queensland. Image © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

Hong Kong Club. Designed 1980-84. A prominent prestressed concrete structure in central Hong Kong. Image © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

Horizon Apartments. Designed 1990-98. 43 storeys of prestressed concrete overlooking Sydney’s harbour. Images © Harry Seidler & Associates Pty Ltd.

Bibliography:

Frampton, K. & Drew, P. (1992) Harry Seidler: Four Decades of Architecture. Thames and Hudson Ltd, London.

Harry Seidler & Associates. (2016) Harry Seidler biography. [Online] Available here. [Accessed: 26th March 2016].

NSW: Office of Environment & Heritage. (2016) Harry and Penelope Seidler House. [Online] Available here. [Accessed: 26th March 2016].