Today, Brutalism maintains its status as a genre of architecture dividing opinion across two clear camps: love it or hate it.

A stark and functionalist style of architecture, Brutalism’s monolithic edifices are repeatedly deemed to be rife with crime and fear. This is an erroneous assumption, one where Brutalism is blamed for the many forms of antisocial behaviour manifested throughout the urban landscape. Indeed opponents of Brutalism will time and again work themselves into a state of frenzy, providing numerous reasons on why Brutalist buildings are ill-fated, offensive, socially inept, confusing and expendable.

The Heygate Estate in south London was completed in 1974 and once housed more than 3,000 people. It was demolished in 2014. Photo via The First Pint.

The Barbican. Photo by James Barr via the Guardian.

Contrast the Heygate’s demise with the hugely influential and successful Barbican Estate in London. Designed in the 1950s by British firm Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, the estate was built between 1965 and 1976. Today, the Barbican complex is one that offers a mix of private, community and public domains.

The Barbican is Europe’s largest multi-arts and conference venue. Photo © This is Global Limited 2016.

Brutalism: An Honest Beauty

In the ‘yes camp’, Brutalism is beautiful. Monolithic and bold, it is an imposing expression of material and form. It is exhilarating and raw, with rough textures emphasising heavy materials and construction. Brutalist buildings are massive and almost always concrete, their shapes at times adopting clever and unusual forms. To its endearing credit, Brutalism is honest and undisguised, naked and apparent, in truth a prepossessing manifestation of modernism. Writing in ‘spiked’, the online current affairs mag, Alexander Adams notes: “Joseph Watson, creative director of the [UK] National Trust, defines Brutalism as a distinct strand within modernism… [and one that adheres] to the truth-to-materials principle of modernism.” (Source)

Hunstanton School ca 1955. Photo © John Maltby via Arup Foresight.

The architectural historian Reyner Banham first used the term ‘Brutalism’ in 1954, in reference to British architects Alison and Peter Smithson’s school at Hunstanton in Norfolk, England. (Source: Architecture.com) Despite the school’s predominantly steel structure, architectural website Bdonline noted that “the honesty of materials and construction central to brutalism was already apparent.” (Source)

The school at Hunstanton was austere; built to a tight budget, using mass-produced and prefabricated materials, it provided an example of the growing British acceptance of modernity in a post World War II age.

Balfron Tower, London. Designed in 1963 by Ernő Goldfinger. Photo by Graeme Maclean via Creative Commons.

Trellick Tower, London. Designed by Ernő Goldfinger and completed in 1972. Image via The Modern House.

The ‘Brut’ in Brutalism

Brutalism became associated with concrete, a powerful material exhibiting much substance and strength. The ‘Brut’ in Brutalism is not, in the misguided belief of many, a reference to the genre’s seeming ‘brutality’. Instead, it relates to Béton brut, that state of raw and unfinished concrete. Using concrete, Brutalist structures were built to a non-human scale, their often frightening facades imposing a level of authoritarianism upon people and their surroundings. Yet in truth, these behemoths were conceived as integral to the betterment of towns and cities, their newness a part of a modern and prosperous society.

Ulster Museum in Belfast, N. Ireland. This Brutalist extension was designed by Francis Pym and opened in 1972. Photo by Simon Phipps via tumblr.

Hayward Gallery, London, was opened in 1968. It was designed by Dennis Crompton, Warren Chalk and Ron Herron. Photo © Art Fund 2016.

Preston Bus Station in Lancashire, England. Built between 1968 and 1969. Photo by Alamy via the Guardian.

Brutalism: Part of the Urban Narrative

Throughout the 1950s, 60s and 70s, Brutalism was an architectural embodiment of ambition, never intended as an abomination. Social strife, poverty and conflict were all factors in its apparent fall from grace. Moreover, Alexander Adams writes in ‘spiked’: “The shabbiness and technical deficiencies of second-rate Brutalist housing schemes during the postwar years have tarnished the style’s reputation.” (Source) The extent to which architects and town planners are responsible for Brutalism’s ill-fated reputation remains part of an ongoing discourse.

The Breuer Building was designed by Marcel Breuer and completed in 1966. The former home of the Whitney Museum of American Art, it is now home to The Met Breuer (part of The Metropolitan Museum of Art). Photo by Ed Lederman via Condé Nast Traveler.

Former Whitney Museum of American Art. Photo by Jerry L. Thompson via Whitney Museum of American Art.

Brutalism is in constant need of champions. In Britain for example, it is estimated that only one hundred “world-quality” Brutalist buildings continue to exist. (Source: spiked) Though clearly unpopular and derided by many, to demolish Brutalist buildings is to erase an important point in architectural history. Brutalism is a part of our urban narrative: one that is arguably more important than today’s architectural propensity to play safe when designing and constructing buildings. The original proponents of Brutalism imagined a utopian future, a commitment to progress and change for the better. Those ideals remain and are embodied in many beautiful, sublime, even haunting, Brutalist buildings. They are undoubtedly worth preserving and celebrating.

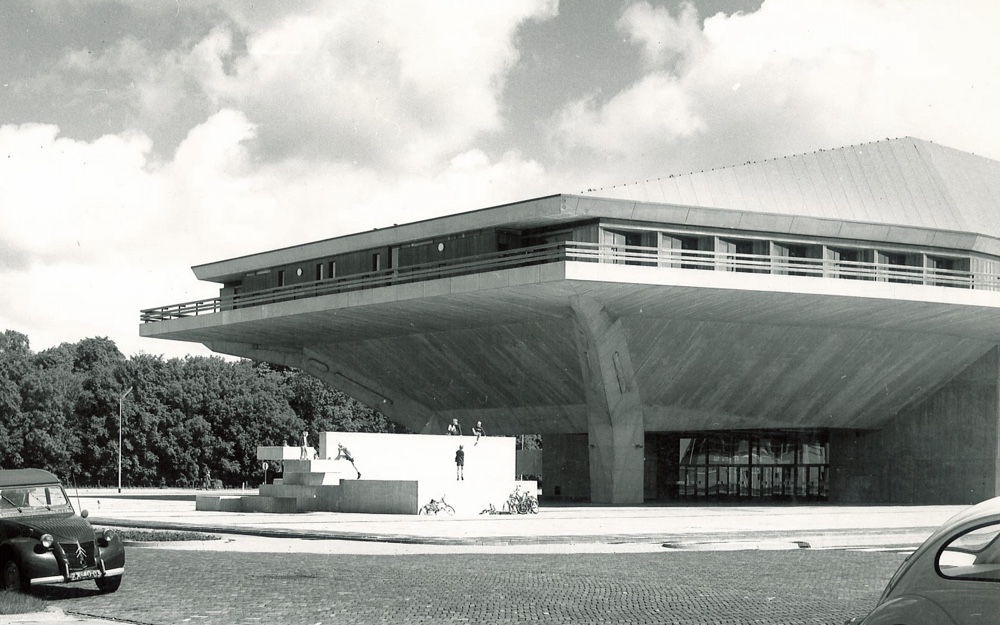

Auditorium at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. Designed in 1966 by architects Johannes Van den Broek and Jaap Bakema. Photo via Broekbakema.

SESC Pompéia in Brazil by Lina Bo Bardi. Completed in 1977. Photo via ArchDaily.

Park Hill, Sheffield

Sheffield’s Park Hill is Europe’s largest (Grade II) listed building.

Built in the post World War II era (between 1957 and 1961), Park Hill was a beacon of optimism, a modernist development intended for a new age of fairness and prosperity. Yet as with many similar ventures, Park Hill would face decline, the victim of poor maintenance, high unemployment, graffiti and crime. Fast-forward several decades and Park Hill is undergoing a mass revival, with redevelopment and refurbishment headed up by Urban Splash in association with architects Hawkins-Brown and Studio Egret West. In a rather unusual addition to Park Hill’s Brutalist facade, Urban Splash added a series of brightly coloured aluminium panels in order to provide a new and distinctive identity.

Park Hill photos © Urban Splash Ltd.