From the mega metropolis to the creeping conurbation, the compact city to the tiptop town, concrete is almost always king of the urban jungle. In constructing roads, buildings, bridges, tunnels – indeed in all manner of structures – concrete is a fundamental foundation, a cornerstone and stalwart.

Deciphering Concrete

Concrete is a compound. Burnt chalk and clay, baked at a high temperature and then ground, form a powder that becomes cement. Concrete is a combination of cement, sand, aggregate (gravel or crushed rocks) and water and is normally reinforced with steel. Grey in color, concrete is an easy, sturdy and generally well-behaved building matter. Over 7.5 billion cubic meters of concrete are produced annually and there is barely a country on earth that has not been touched by this extraordinary material.

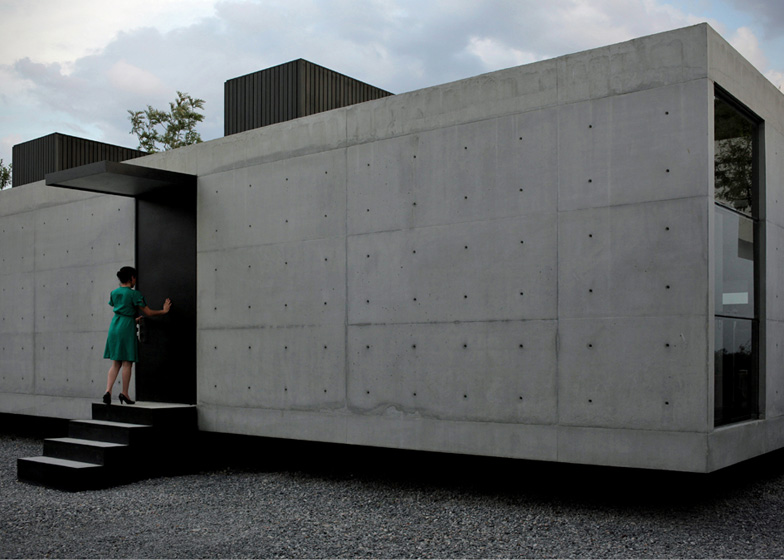

Concrete in a house renovation by Toulouse architects BAST. Image via Deezen.

La Coruña Center For The Arts. Photo © Hector Santos-Diez via ArchDaily.

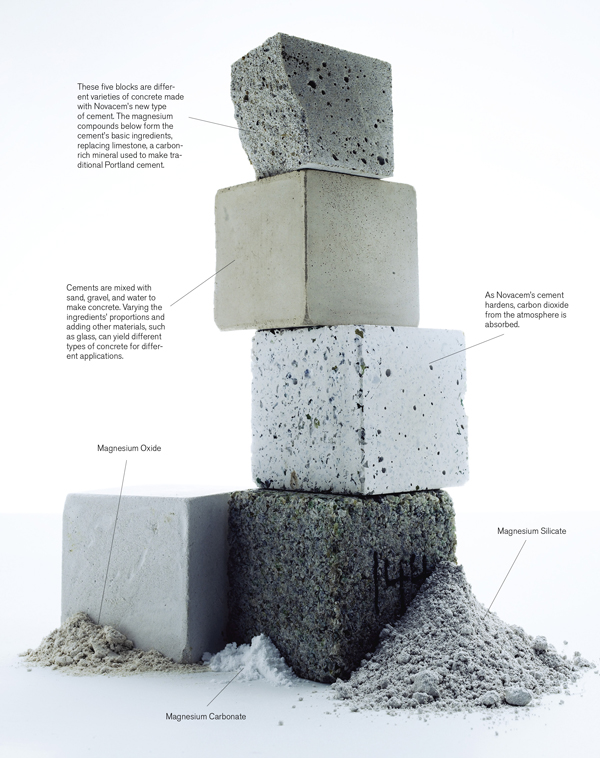

By Nato Welton via MIT Technology Review.

Centro Niemeyer, Avilés, Spain. Photo: © James Ewing Photography via Domus.

An extension to the Herdern Railway Service Facility in Zurich, Switzerland by EM2N. Photo © EM2N.

The Giant’s Causeway Visitor Centre, N. Ireland. Photo © Hufton + Crow via ArchDaily.

Long-Standing, Dramatic Beauty

Concrete has for years been the stuff of utopian dreams. It is an enabler, a thing that has allowed us to build and grow our vast human habitats. Concrete has given us the means to conquer nature or at the very least to hold her at bay. We can witness the dramatic use of concrete in sea walls and dams, in protection against earthquakes and fire safety, to give but a few examples.

Ikehara Dam, Japan. Photo by 河川一等兵 via Wikimedia Commons.

Seawall photo via ClimateTechWiki.

Raw, Edgy & Ergonomic

For some, concrete is ugly and severe, perhaps even intimidating. In the minds of many, concrete symbolizes austerity and division, a material representative of systems such as communism, socialism and the welfare state. Post World War II, particularly the 1950s and 1960s, concrete was utilized in cities to create mass standardized prefabricated housing blocks and public buildings, in the main to deal with a shortage of housing and overcrowding. Often hailed as innovative and futuristic, architects and planners were striving to create new and better ways of living. However these dense concrete blocks, cramped and impractical, would become harbingers of urban decay.

A typical ‘Khrushchyovka’ (a low-cost concrete apartment building) in Yerevan, Armenia. Image © ‘Life in the Caucasus’.

Iconic Concrete Facades

The Aylesbury Estate, a once-monumental residential concrete edifice in south east London, was designed by the architect Hans Peter Trenton. Its construction began in 1963 and the estate was at one time Europe’s largest housing project, the enormous concrete facades and aerial walkways promising new homes and a better way of life for 10,000 people. With the estate’s decline and vilification as “the black hole of London” (Source), demolition is looming and residents are being rehoused. The Aylesbury Estate, as with many monolithic concrete structures across Europe, has become the dystopian poster-child for a broken society.

Aylesbury Estate View. Photo by Mkimemia via Wikimedia Commons.

Route 42 at the Aylesbury Estate. Photo by Sludge G via Wikimedia Commons.

Shaping the World of Tomorrow

Yet for all of its faults, concrete is central to modernity, and love it or loathe it, will continue to find application in architecture and design. With the rubber-stamped approval of some of the world’s foremost architects, from Tadao Ando to the late Oscar Niemeyer, concrete is a material of substance and strength. Its brutalist architecture has both presence and allure, on the one hand functional and on the other offering romantic notions of betterment. London’s Barbican Estate is an example of a place that pays homage to concrete’s capabilities.

The Barbican. Photo © 2015 Barbican Life.

Designed in the 1950s by British firm Chamberlin, Powell and Bon (the estate was built between 1965 and 1976), the entire surface of this concrete residential, retail and arts complex was pick-hammered and hand-finished. The Barbican, with its elevated gardens, provides a fertile micro climate within central London that is on average three degrees warmer than the rest of the city. Mimosa trees can grow there, and if you wander through the Barbican Estate’s grounds, you cannot fail to notice the beauty of its nature. The Barbican complex is one that successfully offers a clearly expressed demarcation between private, community and public domains.

The Barbican. Photo © Lawrence Williams via Barbican Life.

Of course, concrete architecture is not always brutal. Many of today’s finest structures, particularly residential, are built with concrete. Striking, aesthetic and elegant, they are examples of concrete’s universality of use and appeal.

Alpine concrete house by Nickisch Sano Walder Architects. Photo by Gaudenz Danuser via Dezeen.

Casa 2G concrete house in Mexico by Stación-ARquitectura. Image via Dezeen.

The House Of Silence By FORM/Kouichi Kimura Architects in Shiga, Japan. Photo © Kei Nakajima via FORM/Kouichi Kimura Architects.

X House by Cadaval & Solà-Morales. Photo © Cadaval & Solà-Morales.

Concrete interior. Photo by Giorgio Possenti via Design Milk.

The beauty of concrete is found in its gravitas, its poise and its many good intentions. Concrete is a material to be celebrated and applauded, and its abundance should not negate its value or versatility. Rather concrete’s manmade form is working for the amelioration of modern societies, striving to ensure places and spaces are smarter, cleaner, happier and healthier for all.